The US Department of Energy (DOE) wears many hats.

Finding its origins in the Manhattan Project, before officially being established in 1977 under President Jimmy Carter, the DOE now handles everything from nuclear weapons development and cutting-edge scientific research, to the decarbonization of the grid. And that is only the tip of the iceberg.

Ann Dunkin was CIO of the DOE for close to four years, leaving her post when the Biden administration departed office in January. Following her resignation, Dawn Zimmer briefly held the role, until the new government replaced her with a SpaceX network engineer, Ryan Riedel, in February 2025.

DCD spoke to Dunkin while she was still in post, discussing the department's diverse portfolio of responsibilities, and the variety of challenges that come with it. Her successor will likely have to meet these challenges with a vastly reduced workforce, with reports suggesting up to 2,000 DOE staff could lose their jobs as part of so-called efficiency savings being enacted across US government departments by DOGE, the organization led by Elon Musk.

The original version of this interview can be found in issue 55 of DCD Magazine. Read it free of charge here.

DOE CIO's biggest challenge

The question of what is the biggest challenge for the DOE CIO is a “huge” one, Dunkin says. One of the more obviously complex areas is the nuclear mission, not least because the consequences of something going wrong are significant.

“Obviously, we have a nuclear mission, and that involves trying to ensure that nuclear secrets and capabilities don’t get into other countries where they don’t already exist,” Dunkin explains.

“We do a lot of things around developing technologies to help identify radiological components and protecting the intellectual assets to ensure that those are not transferred to other countries. We also maintain the nuclear stockpile.

“We thought we were done at some point, and then we realized that we need to replace those weapons with some regularity. I think we all hoped that post-Cold War, the world would become a safer place where there was less nuclear threat. But with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the nuclear threat changed dramatically, and now we have the rise of other nuclear powers. So we need to maintain that deterrent.”

From a cybersecurity angle, there is a need to protect those assets from hackers and, as a result, many of them sit on classified networks. Understandably, the ins and outs of those networks were not shared by Dunkin.

The need for resilience and cybersecure systems is also extremely pertinent to the DOE’s role in managing the power grid, which it does across 36 states.

Dunkin draws a comparison to the CrowdStrike outage of July 2024 that took down hospitals, planes, emergency services, and other critical services globally.

“While the CrowdStrike outage wasn’t a cybersecurity event, you could see a cybersecurity event that looks a lot like that,” explains Dunkin, noting, however, that the US power grid was not impacted by the CrowdStrike incident due to a policy in which “nobody deploys untested patches.”

“The power grid was up and running, which obviously made it a lot easier for everyone else to solve all the other problems,” she adds.

Dunkin does reiterate, however, that the DOE is “not 100 percent confident,” in its defenses, and adds that “no one wants to challenge the bad guys to come together and have a go.”

The DOE, besides its obvious role of being in charge of energy policy and the like, is well known for sponsoring more physical science research than any other federal agency, and much of this is conducted through its system of 17 national laboratories.

Being at the forefront[ier] of supercomputing

Dunkin is a pretty firm believer in the importance of on-premise high-performance computing (HPC), though she notes that she is not in charge of procurement decisions.

“I am convinced that to maintain leadership in capability computing - where we actually advance HPC - we need to do it on-premise,” she says. “Not everyone agrees with me, but I really believe that's a capability we need to own, grow, and develop in the DOE.”

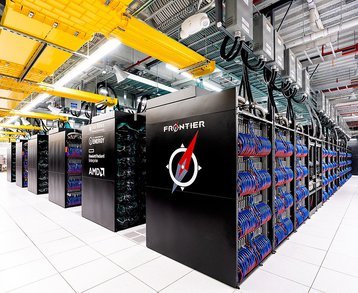

The DOE undeniably does take that mission seriously. Frontier, housed at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, took the top spot on the Top500 list, which ranks the world's most powerful supercomputers, in December 2023 with a performance of 1.353 exaflops (HPL).

Since then El Capitan, housed at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, has surpassed Frontier and now tops the table, with Aurora, hosted at the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility in Illinois, in third place.

The DOE also uses cloud-based HPC, for what Dunkin refers to as capacity computing, adding that in some cases this will be done via a hybrid model, starting with the on-premise HPC and the “bursting” into the cloud.

Regardless of whether it is cloud-based or on-prem, Dunkin argues that “what we do know is that supercomputing is critical to our mission.”

She explains: “All science is computational now, and the vast majority of our programs are better because we are able to deliver more computing capacity. Even if it's a physical experiment, we're modeling that system to try and understand the best experiments to do, and then we're analyzing data from those experiments to better understand our results.”

An example of such research Dunkin offers is nuclear fusion. Often viewed as the ultimate power source, fusion has the potential to provide limitless sustainable power by mimicking conditions in the sun, fusing light atoms into heavier ones.

Though several companies are working on fusion devices and promising to turn the theory into reality, current working assumptions suggest that it remains years, if not decades, away from fruition.

Still being worked on by scientists around the world, Dunkin states that there is a “direct correlation” between the success of fusion experiments, and the computing capacity available.

Beyond traditional HPC, DOE is also hedging its bets on quantum aiding in the clean energy mission.

The near future of research

Quantum computing is another technology that is still a work in progress, with many different approaches being explored. For Dunkin, this is part of what makes the DOE’s work so exciting.

“One of the great things about what we do is the diversity of the labs and the diversity of the bets,” she says. “We have at least five labs working on quantum with different approaches. I’m not smart enough to know which approach is going to be the best - and that’s kind of the whole point - but we get to make lots of bets, and we will get to see which bets pay off.”

Among those bets, the DOE is looking at different materials to build qubits - or quantum bits, the basic unit of quantum information - and other projects looking at how to build larger quantum systems and scale them. “I don’t know who's going to win in terms of getting there, but we’ve got lots of smart people working on it and how we are going to commercialize that work,” Dunkin says.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is also central to the DOE’s work. In January 2024, the department’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Washington teamed up with Microsoft to find candidate battery materials. This work, using AI and traditional HPC via the Azure Quantum Elements (not related to quantum computing) service, reduced the possibilities of materials from millions to only a few options.

Starting with 32 million inorganic materials, AI models cut that down to 500,000, and HPC shaved it even further to just 18 options. “There’s a lot of power in artificial intelligence,” says Dunkin.

The irony, however, of the resource-draining nature of these powerful machines, is not lost on Dunkin.

“AI is a huge power sink, and training generative AI models in particular has shown itself to be hugely costly and energy intensive,” she says. “It’s a bit of a paradox, in that doing all this great research that can ultimately reduce our climate impact requires energy. We believe that all the energy we use has a huge payback in the end, and we are doing the best we can to use renewables where possible in the meantime.”

The DOE is certainly not 100 percent renewable, but efforts are made to improve the efficiency of its labs, plant sites, and headquarters. An example is that the agency generates wind power on-site at its Amarillo site, and often deploys solar panels at locations. Dunkin jokingly adds: “We also don’t mine Bitcoin.”

AI is also being used to help bring more renewable energy onto the grid, with the DOE deploying the technology to deal with permitting complexities that have caused projects to stall.

Currently, there is a massive queue of grid interconnection applications - having grown some 27 percent in 2023. As of April 2024, around 2.6TW of planned power projects had joined the interconnect queue which is around twice the US’ existing generator capacity. Of those requests, 95 percent are for renewable power sources.

“You've got local, state, and federal agencies that, depending upon where you are, may have an opinion about your power, where they're running that power or providing additional capacity on the grid to get that power online,” she says.

“We have a project we're working on right now to help folks speed up permitting with AI solutions to help people understand better what they need to do, and how to get that permit.”

In addition to permitting, one unique area Dunkin oversees in her role as CIO at the DOE is the handling of wireless spectrum necessary for “grid timing.” The spectrum is kept isolated to avoid interference and is essential to ensuring connectivity to keep the grid up and running and the power moving in the right places.

“If you look at the grid, it's incredibly complicated now compared to what it was when we started bringing power into the country 100-something years ago. We have to keep all the power moving in the right direction, to not accidentally energize a line that's not supposed to be energized, all those things, and we need to be able to time the grid, and that requires wireless to do that.

“We have some dedicated spectrum we use for that, which is owned by the government and that’s the primary need. We also use it for general wireless communications between those sites, for example, if we need to shut down a transformer or power to a line. Those signals need to get through or someone could get hurt or we could take down parts of the grid.”

A problem of distribution

The undeniable fact is that the DOE has a massively distributed footprint, and this creates a logistical and operational challenge, both in terms of reaching 100 percent renewable energy without the national grid doing so, but also in its IT infrastructure.

At this point, the vast majority of the department’s everyday enterprise computing is in the cloud, with Dunkin noting that the vast majority of its data centers that remain open are focused on mission computing.

The agency is also not tied to one cloud provider - in fact, Dunkin suggests the DOE uses “probably every cloud you can think of,” adding that they are making a big investment in the “Big Three” - Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud.

There isn’t a plan for “centralization,” simply because the DOE is so distributed, and in many cases, it simply wouldn’t be appropriate. It makes sense for plants and sites to have their own cloud.

With the department's origins stretching as far back as the Manhattan Project and the Atomic Energy Commission, there remain some legacy applications handled by the DOE, but because the agency does not have many public-facing applications, modernization isn’t quite as large a challenge as it might be for other federal agencies.

“The biggest public-facing application that we have is the Energy Information Administration (EIA), which puts out statistical data,” says Dunkin. “They post reports, and what happens is everyone wants to look at the EIA’s data one day, but the traffic dips pretty quickly after that.

“We are working to the EIA to move to the cloud and modernize, and the CIO over there is doing really good work to make that transition from what used to be on-premise data centers, to commercial data centers, and then to the cloud.”

The DOE is also working on moving its HR systems to the cloud, which should be completed in the next 12 to 18 months.

Dunkin notes that the agency is helped by the fact that the DOE’s labs do research for other public sector entities and private companies, even other governments, all of which pay taxes to fund the labs’ overheads. “For the most part, they have pretty modern IT systems,” Dunkin explains.

“This is a little bit less at some of our nuclear manufacturing sites, but definitely our modernization challenges are much smaller than another similar-sized government organization.”

Overall, the sheer complexity and quantity of work handled by the office of the CIO at the DOE is not lost on Dunkin, but she seems mostly excited by the fact.

“I get to see lots of amazing stuff and support it. It is really complex, and it's bigger than any place I’ve been [CIO of] before. We have a combined IT and supercomputing budget of almost $6 billion, and we are tackling really complicated problems - building nuclear weapons, trying to solve nuclear fusion, and so on.

“An organization managing just one of those problems would be significant, and we have them all.”

Dunkin’s previous CIO experience includes at the County of Santa Clara, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the Palo Alto Unified School District, and other related roles.

Despite this, Dunkin recalls someone telling her she has the coolest CIO job across the federal government.

“I’m not sure I can disagree with that,” she says.

This original version of this interview appeared in DCD Magazine issue 55. Read the magazine in full, free of charge, here.